Operating Systems 2015F Lecture 2: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==Video== | ==Video== | ||

The video for this lecture [http://homeostasis.scs.carleton.ca/~soma/os-2015f/lectures/comp3000-2015f-lec02-09Sep2015.mp4 is now available]. Note that this lecture was pre-recorded. | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

Latest revision as of 21:38, 8 September 2015

Video

The video for this lecture is now available. Note that this lecture was pre-recorded.

Notes

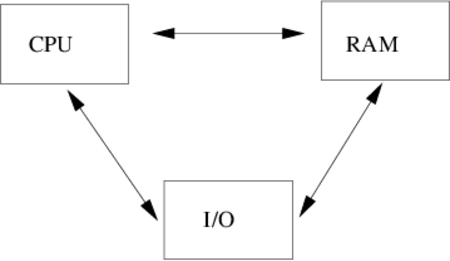

Very abstract view of a computer:

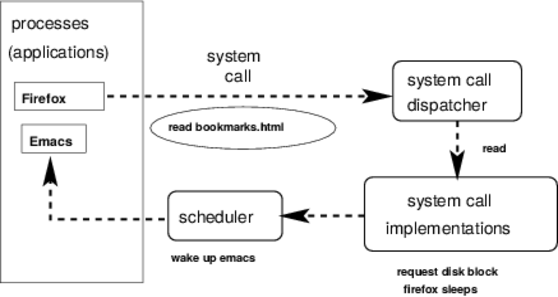

Flow of control for a system call:

Key Questions:

- What is a system call, really?

- How are programs separated from each other?

- What is this "scheduler" anyway?

System calls are the interface between a process and the operating system kernel. They are like function calls, but they are not function calls (although they may be wrapped in library function calls).

Classic system calls:

- files: open, read, write, close

- process control: fork, execve, exit

- memory: sbrk

- networking (socket calls)

Key idea: CPU privilege levels

- applications run in "user mode", lowest level of privileges

- no direct access to I/O devices

- no ability to change amount of RAM

- cannot control how often it has the CPU

- Operating system runs at higher privilege

- gets privileges because it runs first (at boot)

- specifically, the OS kernel runs in "supervisor mode"

- can control CPU, RAM, and I/O devices

- kernel maintains control by setting interrupt registers (will explain more later)

So why isn't a system call a function call?

- function calls involve references to specific memory locations

- processes cannot directly see kernel memory

So what does an application do instead to make a system call?

- executes a special CPU instruction (software interrupt)

- cannot be done outside of assembly language without special support from the compiler

Concepts that I think are unclear:

- mounting

- strace

- system calls