COMP 3000 Essay 2 2010 Question 11

Virtualize Everything But Time

Article written by Timothy Broomhead, Laurence Cremean, Julien Ridoux and Darrel Veitch. They are working for the Center for Ultra-Broadband Information Networks (CUBIN) Department of Electrical & Electronic Engineering at the University of Melbourne in Australia. Here is the link to the article: [1]

Background Concepts

The next time you notice one stranger ask another for the time and you see them check their watch, try this experiment: immediately ask too. Chances are the person will check their watch again. Why? Human internal clocks are notoriously unreliable. Our sense of time contracts and expands all day long. We seem to believe that a definitive report of time can only come from some mechanical or electronic source. So social norms require that the watch owner provides you with two things: 1) the time, and 2) a gesture of external authority, i.e. a glance at their watch.

The story of time inside a virtual machine is almost as unreliable as our own internal clocks. How much time has elapsed since a VM client got the CPU's attention? At the best of times there's no way for it to guess because it wasn't actually running. If the VM was suspended and migrated from one physical host to another its concept of time is even worse. This paper is about how a computer glances at its metaphorical watch, and what kinds of timepieces it has at hand.

To better understand this paper, it is very important to have a good understanding of the general concepts breached in it. For example, we all know what clocks are in our day-to-day life but what are they in the context of computing? In this section, we will describe concepts like timekeeping, hardware/software clocks, the advantages and disadvantages of the different available counters, synchronization algorithms and explains what is a para-virtualized system.

Timekeeping

For thousands of years, men have tried to find better ways to keep track of time. From sundials to atomic clocks, they were all made for the specific purpose of measuring the passage of time. This is not so different in computer operating systems. It is typically done in one of two ways: tick counting and tickless timekeeping[2]. Tick counting is when the operating system sets up an hardware device, generally a CPU, to interrupt at a certain rate. So each time one of those interrupts are called(a tick), the operating system will keep track of it in a counter. That will tell the system how much time has passed. In tickless timekeeping, instead of the OS keeping track of time through interrupts, a hardware device is used instead starting its own counter when the system is booted. The OS simply reads the counter from it when needed. Tickless timekeeping seems to be the better way to keep track of time because it doesn’t hog the CPU with hardware interrupts however, its performance is very dependent on the type of hardware used. Another disadvantages is that they tend to drift and can cause inaccuracy. I will explains those drifts later. But both of these are just counters. They don’t know what is the actual real-time. To remedy that, either a computer gets its time from a battery-backed real-time clock or it queries a network time server(NTP) to get the current time. The computer can also use software in the form of a daemon that will run periodically to make adjustments to the time.

Clocks

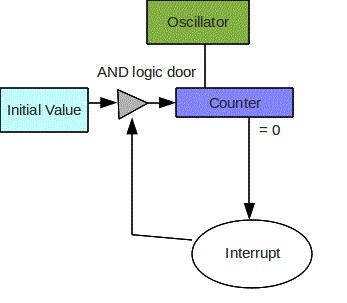

Computer “clocks” or “timers” can be hardware based, software based or they can even be an hybrid. The most commonly found timer is the hardware timer. All of the hardware timers can be generally described by this diagram where some have either more or less features:

Diagram1. Timer Abstraction

This diagram nicely represents how tick counting works. The oscillator runs at a predetermined frequency. The operating system might have to measure it when the system boots. The counter starts with a predetermined value which can be set by software. For every cycle of the oscillator, the counter counts down one unit. When it reaches zero, its generates an output signal that might interrupt the CPU. That same interrupt will then allow the counter’s initial value to be reloaded into the counter and the process begins again. Not all hardware timers work exactly like that. For instance, some actually count up, others don't use interrupts, and yet others don't keep an initial counter. The general principle of hardware counters is the however the same. There is some kind of fixed interval at the end of which the current time is updated by an appropriate number of units (i.e. nanoseconds).

Timers

- PIT is useful for generating interrupts at regular intervals through its three channels. Channel 0 is bound to IRQ0 which interrupts the CPU at regular intervals. Channel 1 is specific to each system and Channel 2 is connected to the speaker system. As such, we only need to concern ourselves with Channel 0. [3]

- CMOS RTC, also known as a CMOS battery, allows the CMOS chip to remain powered to keep track of things like time even while the physical PC unit has no source of power. If there is no CMOS battery on the motherboard, the computer would reset to its default time each restart. The battery itself can die, as expected, if the computer is powered off and not used for a long period of time. This can cause issues with the main OS as well as the VM. [4]

- Local APIC handles all external interrupts for the processor in the system. It can also accept and generate inter-processor interrupts between Local APICs. [5]

- ACPI establishes industry-standard interfaces configuration guided by the OS and power management. It is industry-standard through its creators, Intel, Microsoft, Phoenix, Hewlett Packard and Toshiba. Its power management includes all forms: notebooks, desktops, and servers. ACPI's goal is to improve current power and configuration standards for hardware devices by transitioning to ACPI-compliant hardware. This allows the OS as well as the VM to have control over power management. [6][7][8]

- RDTSC is based on the x86 P5 instruction set and perform high-resolution timing, however, it suffers from several flaws. Discontinuous values from the processor are caused as a result of not using the same thread to the processor each time, which can also be caused by having a multicore processor. This is made worse by ACPI which will eventually lead to the cores being completely out of sync. Availability of dedicated hardware: "RDTSC locks the timing information that the application requests to the processor's cycle counter." With dedicated timing devices included on modern motherboards this method of locking the timing information will become obsolete. Lastly, the variability of the CPU's frequency needs to be taken into account. With modern day laptops, most CPU frequencies are adjusted on the fly to respond to the users demand when needed and to lower themselves when idle, this results in longer battery life and less heat generated by the laptop but regretfully affects RDTSC making it unreliable. [9]

- HPET defines a set of timers that the OS has access to and can assign to applications. Each timer can generate an interrupt when the least significant bits are equal to the equivalent bits of the 64-bit counter value. However, a race case can occur in which the target time has already passed. This causes more interrupts and more work even if the task is a simple one. It does produce less interrupts than its predecessors PIT and CMOS RTC giving it an edge. Despite its race condition, this modern timer is improvement upon old practices. [10]

Guest Timekeeping

Guest timekeeping is done using the same general methods as any computer timekeeping, using either tick counting or tickless systems. Where the two begin to differ, however, is that a host operating system is able to communicate directly with the physical hardware, while the guest operating system is unable to do so, having to communicate with the host system that it wants to communicate with the hardware. Having to do this is the greatest source of the guest operating system's clock losing accuracy, or more simply called drifting.

Sources of Drift

When a guest operating system is started, its clock simply synchronizes with the host's – some virtual machines such as VMware also do this when it is resumed from a suspended state, or restored from a snapshot – so it is easy to think that, since it starts off correctly the guest's clock will continue to be correct. That is, of course, incorrect. The first source of drift is simply due to the drift a host incurs in its own timekeeping. A clock is almost never entirely accurate, having a slight error due to the effects of ambient temperature on oscillator frequency, even on the host system. Since the guest communicates with the host in order to keep track of its time, an error in the host's time is not only passed on to the guest, but because the host is trying to correct its own time the guest's request for a count is given slightly less priority, making it yet again lose accuracy. The larger the drift in the host, the larger the drift in the guest, as the host's drift simply compounds the issue.

Aside from the host's own drift, the other cause of drift in the virtual environment is the fact that the it is treated like a process by the host. In and of itself this doesn't seem like a problem, but because of it it can be denied the CPU time required, or allocated less memory than needed. With restricted CPU time, it's easy for the requested ticks or requested read of a counter to pile up and create a backlog of requests, or simply receive the requested data late enough to throw its clock off. With memory, if the virtual environment does not have enough allocated to it by the host it can run into the problem of swapping out pages that are needed soon. Swapping the pages back in will momentarily bring the entire virtual environment to a halt, so ticks are missed and the clock falls behind.

But perhaps the largest source of errors in virtual timekeeping come from the fact that their algorithms were not designed for virtual environments. They assume a more predictable physical world and so their compensations can be like oversteering on an icy road.

Impact of Drift

The impact of drift essentially boils down to round-off errors and lost ticks. The practical impact of drift, however, is quite apparent in any automated system. For a relatable real-world example, though not in a virtual environment, in a factory's assembly line, the machinery is finely tuned to do its own specific part at certain intervals, and it generally does so with impressive efficiency. If the clock in the system were to drift, however, a specific machine may move too soon or too late, bringing the line to a potentially catastrophic halt. In a virtual environment, drift is a bit more subtle, as one result of it could be skewed process scheduling – some schedulers give a certain amount of time to a process before moving on, but if the guest's time has drifted substantially, when it tries to correct its time it could give more or less time to the processes in the scheduler.

Compensation Strategies

There are a number of compensation strategies for dealing with drift, depending on the cause of it. If the problem is due to CPU management issues, then the host can give more CPU time to the virtual machine, or it can lower the timer interrupt rate – or simply use a tickless counter. If it is due to a memory management issue, allocating more memory to the virtual environment should prevent the system from needing to swap out page files so often.

If the issue is from neither of those, but simply due to the inevitable lag when the guest communicates with the hardware via the host, then there are other methods to correct the drift. Most systems natively have algorithms built in to correct the time if it gets too far ahead or behind real time, though they are not without their own faults; if the time is set ahead when catching up, the backlog of ticks it has built up may not be cleared, so it could potentially set itself ahead multiple times until the backlog is dealt with. Tools built into the virtual machine itself can also deal with drift to an extent, as VMware Tools does. This kind of tool checks to see if the clock's error is within a certain margin. If it exceeds the margin, then the backlog is set to zero – to prevent the issue mentioned with the native algorithms – and resynchronizes with the host clock before the guest goes back to keeping track of time as it normally would.

Research problem

Today, the use of the Network Time Protocol and of daemons like ntpd is the dominant solution for accurate timekeeping. In optimal conditions, the ntpd can be very good but these situations rarely happen. Network congestion, disconnections, lower quality networking hardware and unsuspected system events can create offsets errors in the order of 10‘s or even 100 milliseconds(ms). [11] For demanding applications, this is neither robust or reliable. One way to enhance the performance of ntpd would be to poll from the NTP server more often as this would reduced the offset error but unfortunately, this would increase the network traffic which could cause network congestions which would raise the offset error. So this won’t work.

Another problem with current system software clocks using NTP(like ntpd), is that they provide only an absolute clock.[12] So for applications that deals with network managements and measurements, this is unsuitable. Why? Because NTP focus on offset and not on hardware clock oscillator rate. For example, when calculating delay variations, the offset error doesn’t change anything to the calculations but the clocks’ oscillator rate variation does affect it. So having a more accurate timestamp would make those calculation more precise. Which mean we would need another system software clock.

In virtualization(in this case Xen), when migrating a running system from one system to another can cause issues and this is again caused by the ntpd daemon. By default, each guest OS runs its own instance of the ntpd daemon. So the synchronization algorithm keeps track of the reference wallclock time, rate-of-drift and current clock error, which are defined by the hardware clock on the system. So when migrating the virtualized OS to another system, the ntpd state is saved and when it is enabled again on the new system, thats where the problems starts. Because no two hardware clocks drifts the same way or have the exact same wallclock time, all the information traced by the daemon are all of a sudden inaccurate. This could prove disastrous to the system. This could go from a slowly recoverable error to one where ntpd might never recover, making the virtualized OS unstable.

Contribution

The authors of this timekeeping paper have done previous work exploring the feed-forward and feedback mechanisms for clock algorithm adjustment in non-virtual systems [7][8]. The RADclock algorithm (Robust Absolute Difference) was originally explored to address the drift resulting from NTP's feedback algorithm, and how non-ideal network conditions (a circumstance that is quite common) can have serious effects. In their original paper they improved network synchronization using the TimeStamp Counter (TSC) register a system call introduced in Pentium class machines as a source for a CPU cycle count. The use of a more reliable timestamp and counter provided "GPS-like" reliability in networked enviroments.

This new paper seeks to take a similar approach in a virtual machine setting where VM migration can cause much more severe disruption than simply lost UDP packets. Rather than use TSC calls (rdtsc() in [8]) they tried several clock sources, seeking to eliminate variability from power management and CPU load when setting raw timestamps for use in guest machines.

The paper makes several references to feed-forward and feedback mechanisms, and so a quick discussion of these control theories is in order. In feed-forward mechanisms, inputs to a process or calculation may be modified in advance, but the resulting output plays no part in subsequent calculations. In feedback mechanisms (such as NTPd) inputs to a calculation can be modified by outputs from previous ones. As a result, feedback mechanisms carry state from one step to the next. Since the state of a virtual environment may be rendered inaccurate by so many sources a feedback mechanism as a bad idea. The statelessness of feed-forward mechanisms offers VM migrations a particular advantage since after migration a guest OS can simply discover the actual facts of timestamps rather than try to estimate them from their own invalid state information.

The mechanism the authors used in the Xen environment was the XenStore, a filesystem structure like sysfs or procfs that permits communications between virtual domains using shared memory. Dom0 (Xen terminology for the hypervisor) takes sychronization from its own time server and saves the calculated clock parameters to the shared XenStore. On DomU (Xen for any guest OS) an application would simply use the shared information as a raw timestamp or a time difference. Their extensive testing showed a clear -- if not surprising -- advantage over NTPd.

Critique

It is difficult to critique the authors' work since they did a great job of finding a meaningful set of timestamps and counters and clearly demonstrated an advantage in their field of study. They also compared a number of time sources to ensure that their selection was meaningful and stable. And it's hard to argue with success. Their results approximate the variation that comes from CPU temperature. That's quite impressive.

As a student, one criticism might be that they found quite an obscure way of describing what was at heart a very simple problem (to be fair, this wasn't written for students). If you can't trust your own perception of time, ask the closest agent you can trust -- and make sure they've check their watch. There is no closer source to a VM than its host, so this seemed like an obvious answer.

References

1. "Virtualize Everything But Time" by Timothy Broomhead, Laurence Cremean, Julien Ridoux and Darrel Veitch, 2010. http://www.usenix.org/events/osdi10/tech/full_papers/Broomhead.pdf

2. "Timekeeping in Virtual Machines, Information Guide" from VMWare. http://www.vmware.com/files/pdf/Timekeeping-In-VirtualMachines.pdf

3. "Bran's Kernel Development Tutorial" from Bona Fide OS Developer website. http://www.osdever.net/bkerndev/Docs/pit.htm

4. "What is a CMOS battery, and why does my computer need one?" from the Indiana University's Knowledge Base, 2010. http://kb.iu.edu/data/adoy.html

5. "Multiprocessor Specification version 1.4" from Intel, 1997. http://developer.intel.com/design/pentium/datashts/24201606.pdf

6. "PC Based Precision Timing Without GPS" by Attila Pa ́sztor and Darryl Veitch, 2002. http://www.cubinlab.ee.unimelb.edu.au/~darryl/Publications/tscclock_final.pdf

7. "Robust Synchronization of Absolute and Difference Clocks over Networks" by Darryl Veitch, Julien Ridoux and Satish Babu Korada, 2009. http://www.cubinlab.ee.unimelb.edu.au/~darryl/Publications/synch_ToN.pdf

8. Broomhead, T.; Ridoux, J.; Veitch, D.; , "Counter availability and characteristics for feed-forward based synchronization," Precision Clock Synchronization for Measurement, Control and Communication, 2009. ISPCS 2009. International Symposium on , vol., no., pp.1-6, 12-16 Oct. 2009