COMP 3000 2011 Report: ttylinux

Part 1

Background

The distribution I chose is ttylinux, named for its initial orientation towards TeleTYpewriter, or TTY serial interfaces. It caters itself to a target audience that includes both users, looking either to get older hardware up and running on the web or for a lightweight portable system they can boot off a USB stick, and developers who are either looking for an OS they can use on embedded systems or for one to base their own variant of Linux on. It was initially developed in 2001 by Pascal Schmidt, who focused on getting it running on serial interfaces over networks, but when Douglas Jerome took his place in 2008, the focus of the project moved away from connecting to serial interfaces and towards its intended purpose of being "one of the smallest up-to-date Linux systems that is similar to a larger distribution", as stated on its website.

You can download ttylinux on the [project website], or from one of a number of the mirrors it lists. Derived from scratch, ttylinux has a file system that can be as small as ~8 megabytes, making it as little as ~12 megabytes with the kernel; however, the smallest default install for i686 uses ~25 megabytes.

Installation/Startup

Installation

To test this distribution, I used Oracle VM VirtualBox Version 4.1.0r73009 and created a new VM using the Linux 2.6 presets and 2 gigabytes of storage, and configured it to have 16 megabytes of video memory, 64 megabytes ram and a bridged ethernet device to connect directly through my network's router. I then used the virtual media manager in VirtualBox to mount the ~35 megabyte ut-ttylinux-i686-12.6.iso, which is an image of the most recent version (12.6) of the most minimal i686 compatible install (ut), and booted the virtual machine.

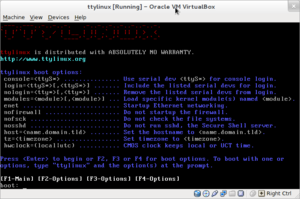

The ttylinux installer initially greeted me with some boot options that allowed a number of settings and services available during the installation to be tweaked, and not needing any of these things to be changed, I pressed enter to begin the installation. It loaded into a version of ttylinux that appears to be about the same as it intends the finished install to look like, and you're presented with a shell prompt where I was able to login with the username 'root', and 'password' for the password. The currently out of date [ttylinux User Guide] explains a method of installation that seems to involve a somewhat manual install process, but in the root user's home directory, I discovered a file named 'install.conf' that explained a (relatively) more user friendly way, and I decided to leave the ttylinux User Guide behind in favour of following this.

To install ttylinux using 'install.conf', I needed to use fdisk to partition the VM's disk first, and I used a similar configuration to the one in the sample that the default 'install.conf' provides. I then used 'vi' to edit the 'fstab' section in 'install.conf' to reflect the the partitions I created, and to test ttylinux's claim of being up to date, I set the filesystems of everything (except for swap, of course) to ext4, resulting in the following configuration:

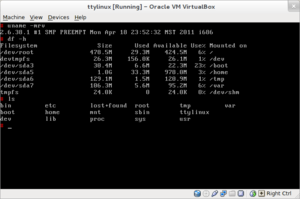

/ P /dev/sda1 512M Linux ext4 swap P /dev/sda2 128M Linux Swap swap /boot P /dev/sda3 24M *Bootable Linux ext4 /home E /dev/sda5 1128M Linux ext4 /tmp E /dev/sda6 128M Linux ext4 /var E /dev/sda7 111M Linux ext4

The rest of the configuration was taken care of entirely within 'install.conf', and it involved setting the desired hostname and host address to 'ttylinux' and 127.0.0.1 respectively, the local timezone to 'EST', some basic network configuration to connect to my network using the bridged network adapter I'd created, and some options for the boot loader including where it should be installed. At this point, I ran 'ttylinux-installer --config=install.conf /dev/hdc', meaning that 'ttylinux-installer' would use './install.conf' as the configuration file and that the install cd was /dev/hdc, and it quickly used the configuration I'd set to format the partitions to the filesystems I'd set for them, created a chroot environment using them and installing ttylinux to in the new environment with the settings I'd chosen.

Once the installation was complete, I used VirtualBox's virtual media manager to remove ut-ttylinux-i686-12.6.iso from the VM's virtual cdrom drive, and rebooted into the new system.

- I'd initially tried playing around with an optional section in 'install.conf' that lets you install specific packages rather than the entire system; however, 'ttylinux-installer' kept failing with errors about missing files when I'd attempt to run it this way, and after a few attempts at some more creative solutions to the problem, I realized that I'd needed to use a full install when I discovered that the files the installer was looking for were in the few packages I'd been comfortable setting it to skip.

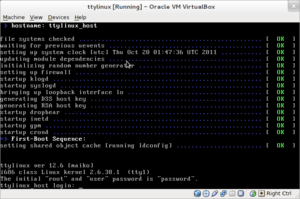

Startup

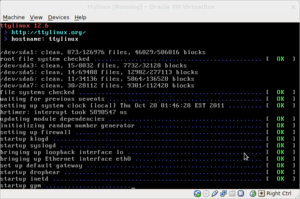

Booting the VM for the first time after installing ttylinux, I was presented with a creatively themed lilo bootloader with a single option to start ttylinux that it selected automatically after a brief countdown. The installed ttylinux system loaded very similar to the install when it booted up, the only major difference I noticed as the text whipped by being that it also checked and mounted the partitions I'd defined in 'install.conf'. Once it had finished loading, I logged in with the same credentials as I had in the installer before promptly using 'passwd' to give the root user a more secure password, and then used 'vi' to edit '/etc/issue' and '/etc/issue.tty' to remove the line that explained the default username and password above each login prompt.

I quickly discovered that I couldn't seem to access the web, and when I checked 'ifconfig' to see that I appeared to have a functional network connection, I used my host OS to find the ip associated with 'www.google.com' and found that my VM was able to ping that, which meant that the problem was likely with '/etc/resolv.conf'. Sure enough, when I checked to see what was wrong with '/etc/resolv.conf' I found that it didn't exist, and after running the command "# echo 'nameserver 192.168.0.1' > /etc/resolv.conf" to create a new one that would use my router's local address to lookup URLs, I tried pinging 'www.google.com' and found that my problem had been fixed.

Everything seemed to be working at this point, and I decided to play around with the system to see what it was like...

Basic Operation

As I stated earlier, the intended purpose of ttylinux is to "make one of the smallest up-to-date Linux systems that is similar to a larger distribution", and while it is small, I decided to take a look at what it was made of to see just how up to date and similar to a larger distribution it was...

I began by taking a look around the file system to see what makes ttylinux tick, and noticed that the '/dev' folder uses udev to manage devices just like nearly all modern distributions of linux; I changed 'SYMLINK+="cdrom"' in '/etc/udev/rules.d/70-persistent-cd.rules' to SYMLINK+="ccdrom"' to see whether rules would work, and sure enough, the link to the cdrom device '/dev/ccdrom' existed in place of '/dev/cdrom' when udev was restarted.

Being up to date means being able to do essential tasks over networks too, so I attempted to download a file with wget, use scp to copy a file to a remote server and log into a remote host using ssh to see if it met those basic networking requirements, and I was pleased to find myself successful in each case. When I noticed that ttylinux has ncurses, I found myself wondering if 'lynks' or 'links' would be available to browse the web, but it turns out that they're both too large to be reasonably considered for inclusion, and that a much more lightweight console-based web browser called 'retawq' was included instead, which albeit much less user friendly, does still seem to get the job done.

Curious how system services worked in ttylinux, I took a look and found that the files in /etc/sysconfig/ each allow for disabling or enabling a service on boot with a variable set to 'yes' or 'no', while some of them also include a variable containing command-line arguments as well. A combination of the 'rc.*' files in '/etc/rc.d/' then appear to be hard-coded to read the values of these variables and decide which services to start and what arguments to give them when they are.

There isn't a huge amount to play with in ttylinux beyond your typical command-line functionality, but its interesting to explore the system and imagine how it could be used to build a port that would be able to meet a set of requirements. Once you've gotten it installed, ttylinux appears to be a solid little system, and aside from needing to add '/etc/resolv.conf' manually, the system started up stable and fully functional straight from the first boot.

Usage Evaluation

To see if ttylinux would really live up to its name, I ran the command "# du -c -m /" and was impressed to find that the full i686 install only took up ~25 megabytes. The ttylinux [project website] reports on its front page that it "has an 8 MB file system and runs on i486 computers within 28 MB of RAM, but provides a complete command line environment and is ready for internet access", but digging a bit deeper I found that this is only true for the 'sm' version that uses a static '/dev' environment and uClib instead of Glibc, unlike the 'ut' version I installed, which the website states that it should have a 24 megabyte filesystem, just like the one I installed.

Command line programs that are typically included in distributions of Linux like 'file', 'man' and 'tree', are left out of ttylinux to conserve space, and while it did take some getting used to initially, not having them in the end slowed me down at times, but it never prevented me from doing what I'd intended to. I was sad to find 'vi' in my $PATH instead of 'vim', which brings much more to the table than a tailing 'm', but in the same respect as the command line applications that weren't included, the decision to choose 'vi' instead is understandable if you consider how much more space 'vim' would have taken up. Taking a look at what ttylinux does include on the other hand, I discovered that it actually has a fairly respectable array of functionality packed in its ~25 megabytes. It uses Busybox to provide a basic structure and set of Unix utilities, then includes a carefully selected collection of programs like 'adduser', 'wget' and 'fuser', which all seem to perform a commonly required task that would either be difficult or impossible to do without. There are also [add-ons] available to provide support for ntfs, the calc utility and an http server, and a [source distribution] exists that includes a build system if additional functionality is required.

Being minimalistic by design, ttylinux is a lean OS that does an excellent job at providing an up-to-date, functional distribution that still manages to be one of the smallest on the block. I can't really fault it for what it doesn't include, and if anyone with a bit more space might want to use ttylinux as a basis to work from, the 'ws' variant available on the [downloads] page includes Alsa and more importantly GCC, so new applications can be built. Thinking back on my experience with ttylinux, the only real critique I can make at this point is for including the package selection feature in the non-beta ttylinux-installer script when it's clearly not yet stable, but overall I really do feel like it does a good job of accomplishing what it set out to do, and that it does it well.

Part 2

Packages for ttylinux follow a naming convention that looks like <software_name>-<software_version>-<system_architecture>.tbz, and they consist of a file structure containing the files and folders to be installed, stored in a tar archive and compressed with bzip2. They can be manipulated by the ttylinux package manager ‘pacman’, which shares its name with the one used by Arch Linux despite appearing to be unique. The following are examples of how you can use pacman to list the packages currently installed on the system, install a package locally and delete packages:

- pacman -qa || # pacman --query-all (list all installed packages)

- pacman -i <package_file> || # pacman --install <package_file> (install a package locally)

- pacman -e <package_name> || # pacman --erase <package_name> (remove a package)

The ‘software catalog’ ttylinux is xtremely minimal. The 'ut' installation image I'm using only contains 17 packages by default, and the installer even allows for those to be deselected (although this ended up breaking the install in v12.6 for me, as mentioned earlier). While 'pacman' is a relatively powerful package manager, capable of generating its own packages as well as using a remote repository; this functionality seems intended mostly in support of ttylinux's aim to be convenient to build new distributions around, and ttylinux itself both lacks a repository of its own and only has 3 official packages offered as add-ons from the ttylinux site. Since ttylinux is so small, I feel each package plays a pivotal point in building it, and should therefore spend less time on each so all of them can be covered...

The following table is the collection of packages included in the base 'ut' installation. Each package is identified before comparing its ttylinux version to the version of the latest stable release (including how long its been since the out of date version came out), and then discussed briefly about what it does and why it might have been included in ttylinux.

BASE PACKAGES The following packages make up the base ttylinux installation of the 'ut' version.

| Package | Latest stable version | Version in ttylinux | Details |

| bash | 4.2 | 4.1 (23 months old) | Contributing 1.2 megabytes of the total ~26 that make up the whole system, BASH wouldn't have been included in ttylinux if it wasn't such an important piece, and while choosing a good shell is always important, it's even more so in cases like this where it's the exclusive user interface. BASH is a solid shell environment with a fairly well rounded way of working that manages to keep most people happy most of the time; it's also stood the test of time along with the rest of GNU, so it's become a bit of a standard in some respects, and therefore makes it the best choice for ttylinux since it can only choose one. BASH is nearly a year out of date in ttylinux, however, this is fair since with its slow release cycle, an update from the version 23 months ago has only just recently come out. |

| busybox | 1.19.3 | 1.18.4 (8 months old) | BusyBox is similar to GNU in that it provides a toolkit similar to the one in Unix, except instead of focusing on trying to have the best tools like GNU already does; it attempts to remain small and portable so it can be installed on virtually anything. All the versions of ttylinux use Busybox except the larger one, which I assume is at least in part so it can also use gcc as well as possibly because storage space is less of an issue for those who go this route. |

| dropbear | 54 | 52 (3 years old) | SSH is an important tool on a network, both for remote management and for interacting with files (using scp). OpenSSH is the current standard for ssh clients and servers, however Dropbear is still quite respectable and leaves a much smaller footprint in comparison, which therefore makes it the ideal choice for ttylinux. It is running a 3 year old version, but the first update in three years was made this month, so you can't really blame ttylinux, and I'm sure the next version that comes out will have this updated |

| e2fsprogs | 1.41.14 | 1.41.12 (6 months old) | The ext2 file systems (including ext3 and ext4) have always been popular in linux, but have been especially so since ReiserFS fell off the map when its developer went to jail for killing his wife; e2fsprogs are the utilities that allow these file systems to be created (using mkfs*), repaired (using fsck*) and an assortment of other administrative capabilities. Including this package in ttylinux wasn't just necessary, but required for setting initially setting the harddrives up, and still remains important after the fact so proper hard drive maintenance can occur. |

| glibc | 12.14.1 | 2.12.1 (15 months old) | |

| gpm | 1.20.6 | 1.20.6 (latest) | |

| iptables | 1.4.12.1 | 1.4.9.1 (15 months old) | |

| valign="top" kmodules | 2003-01-01 | 2.6.38.1 (5 months old) | The kernel itself doesn't belong to a package, but all its associated modules are packed in kmodules, which of course shares the same version number. Its 5 months out of date, which is about the same amount of time since the last version of ttylinux came out, and it seems likely that each release would include the most recent stable kernel. As far as why this package might have been included in distribution goes; kernel modules are key to hardware support and keeping the required memory use at a minimum thanks to their ability to be loaded/unloaded, and while they make senses to be included in pretty well any distribution, they're particularly relevant in a distribution that tries to keep itself as lightweight as ttylinux (at least until a kernel recompile can be done). |

| lilo | 23.2 | 23.1 (12 months old) | |

| module-init-tools | 3.12 | 3.12 (latest) | |

| ncurses | 5.8 | 5.7 (3 years old) | |

| ppp | 2002-04-05 | 2.4.5 (latest) | |

| retawq | 0.2.6c | 0.2.6c (latest) | |

| ttylinux-basefs | 1.0 | 1.0 (latest) | |

| ttylinux-utils | 1.3 | 1.3 (latest) | |

| udev | 175 | 163 (13 months old) | |

| util-linux-ng | 2.20.1 | 2.18 (16 months old) | |

None of the 3 additional packages provided by ttylinux are available through installation, and each provides less than critical yet also useful functionality to the distribution when installed.

ADDON PACKAGES

| Package | Latest stable version | Version in ttylinux | Details |

| thttpd | 2.25b | 2.25b (latest) | |

| ntfs-3g | 2011-04-12 | 2010.10.2 (6 months old) | |

| calc | 2.12.4.4 | 2.12.4.2 (14 months old) | |

References

"ttylinux Homepage" Minimal Linux. Web. 19 Oct. 2011. <http://www.minimalinux.org/ttylinux/> "ttylinux User Guide" Minimal Linux. Web. 18 Nov. 2011. <http://www.minimalinux.org/ttylinux/Documents/single/temp.html>